Case Series/Study

(CS-116) Massive Keloid Excision of the Posterior Scalp with Salvaged Full-thickness Skin Graft: A Case Report

Friday, May 2, 2025

7:45 PM - 8:45 PM East Coast USA Time

Cameron Belding, MD; Laurel Adams, BS; Julia McGee, BS; Molly Gaffney, BS; Leely Rezvani, MD, MS; Abigail Chaffin, MD, FACS, CWSP, MAPWCA – Tulane Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

Introduction: Keloid scars result from excessive collagen production and fibroblast proliferation following dermal injury or inflammation, commonly affecting African Americans. In severe cases, keloids significantly decrease quality of life due to their disfiguring appearance and because they can be painful, pruritic, and chronically infected.1 Treatments include intralesional corticosteroid injections, immunomodulators, cytotoxic agents, lasers, and cryotherapy.2 Surgery may become necessary in recurrent keloids resistant to medical management.2

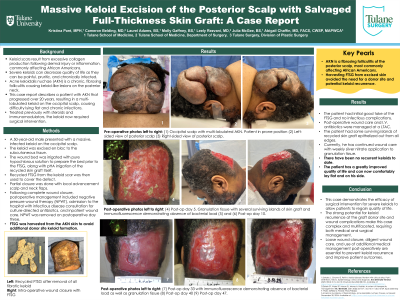

This case report describes a patient with acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN), a chronic, fibrosing folliculitis causing keloid-like lesions on the posterior neck.3 This patient’s AKN progressed over 20 years, resulting in a multi-lobulated keloid on the occipital scalp, causing difficulty lying flat and chronic infections. Surgical excision followed by recycled full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) reconstruction of the scalp was performed.

Methods: A 50-year-old male presented with a massive keloid on the occipital scalp, treated previously with steroid injections and immunomodulators. The keloid became extensive and painful, necessitating surgical intervention. During the procedure, the fibrotic, infected keloid was excised en bloc to the subcutaneous tissue. Subsequently, recycled FTSG from the keloid scar was soaked in hypochlorous acid and then used to cover the defect. Partial closure was done with local advancement scalp and neck flaps. Following complete wound closure, postoperative management included negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), admission to the hospital with infectious disease consultation for culture-directed antibiotics, and inpatient wound care. NPWT was removed on postoperative day three. FTSG was harvested from the AKN skin to avoid additional donor site keloid formation.

Results: The patient had initial good take of the FTSG and no infectious complications. Small surgical dehiscence wounds are being managed outpatient and there have been no recurrent keloids to date.

Discussion: This case demonstrates the efficacy of surgical intervention for severe keloids to allow patients to regain quality of life. The strong potential for keloid recurrence at the graft donor site and wound complications make this case complex and multifaceted, requiring both medical and surgical management. Loose wound closure, diligent wound care, and use of additional medical management post-operatively are essential to prevent keloid recurrence and improve patient outcomes.

This case report describes a patient with acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN), a chronic, fibrosing folliculitis causing keloid-like lesions on the posterior neck.3 This patient’s AKN progressed over 20 years, resulting in a multi-lobulated keloid on the occipital scalp, causing difficulty lying flat and chronic infections. Surgical excision followed by recycled full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) reconstruction of the scalp was performed.

Methods: A 50-year-old male presented with a massive keloid on the occipital scalp, treated previously with steroid injections and immunomodulators. The keloid became extensive and painful, necessitating surgical intervention. During the procedure, the fibrotic, infected keloid was excised en bloc to the subcutaneous tissue. Subsequently, recycled FTSG from the keloid scar was soaked in hypochlorous acid and then used to cover the defect. Partial closure was done with local advancement scalp and neck flaps. Following complete wound closure, postoperative management included negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), admission to the hospital with infectious disease consultation for culture-directed antibiotics, and inpatient wound care. NPWT was removed on postoperative day three. FTSG was harvested from the AKN skin to avoid additional donor site keloid formation.

Results: The patient had initial good take of the FTSG and no infectious complications. Small surgical dehiscence wounds are being managed outpatient and there have been no recurrent keloids to date.

Discussion: This case demonstrates the efficacy of surgical intervention for severe keloids to allow patients to regain quality of life. The strong potential for keloid recurrence at the graft donor site and wound complications make this case complex and multifaceted, requiring both medical and surgical management. Loose wound closure, diligent wound care, and use of additional medical management post-operatively are essential to prevent keloid recurrence and improve patient outcomes.

.jpg)